You’re an FY1 on shift in the Emergency Department and one of your patients has suddenly become very breathless. What do you do? Panic… Run to find your consultant… Try and find your second-year respiratory lecture notes…

Or, assess and manage them in a structured approach to acutely unwell patients?

An A-E, or ABCDE, assessment is a method of assessing and stabilising a patient in a stepwise approach - in order of priority of the things that will cause the most harm. You can perform an A-E assessment on any unwell or deteriorating patient to help you ascertain what’s going on.

When performing an A-E assessment:

“Hello, are you OK?”

Is the patient talking to you? If they’re responding to you, you know their airway is patent. Ensure to speak loudly into each ear in case the patient is deaf on one side. If you get no response, give a painful stimulus using trapezius squeeze or sternal rub to see if they respond to pain.

Always call for help urgently in an unresponsive patient.

Indicative of an airway obstruction.

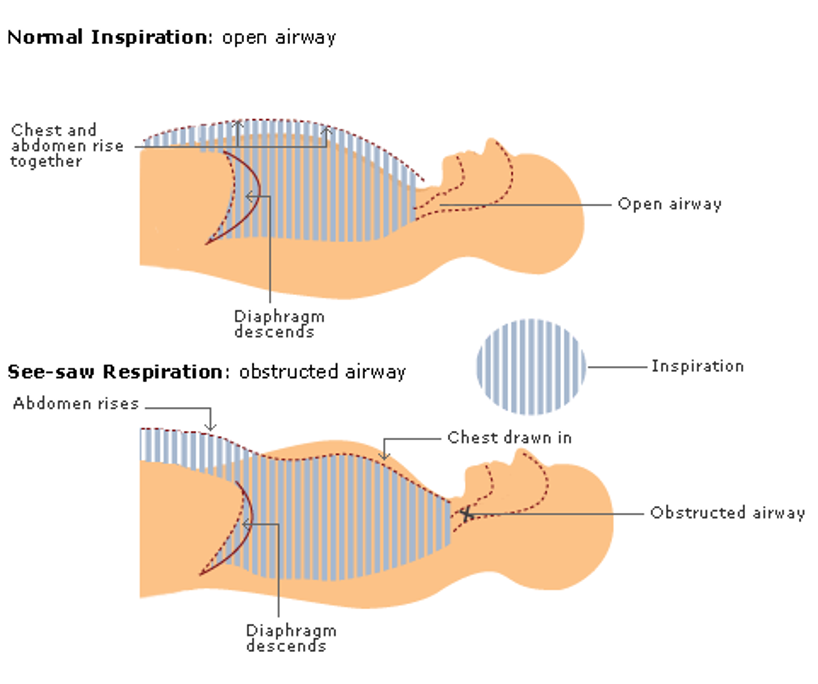

In inspiration, the diaphragm descends reducing intrathoracic pressure. During normal breathing with a patent airway this causes the external air (at a relatively high pressure) to be drawn into the lungs. The chest wall expands as the lungs fill with air

When the airway is obstructed, the diaphragm still descends, and the intrathoracic pressure is reduced. But this time no air can be brought in through the airway. Instead, the reduced pressure sucks the chest wall inwards. The lowering of the diaphragm gives the impression of the abdomen distending.

This is see-saw breathing - a paradoxical movement where the chest wall gets sucked inwards during inspiration.

Check in the patients mouth for a visible obstruction such as a foreign body, vomit or secretions.

Place your cheek over the patients mouth

Absent breath sounds indicate a complete obstruction.

Additional breath sounds indicate a partial obstruction

A noisy, high-pitched, sound due to obstructed airflow in the larynx/trachea.

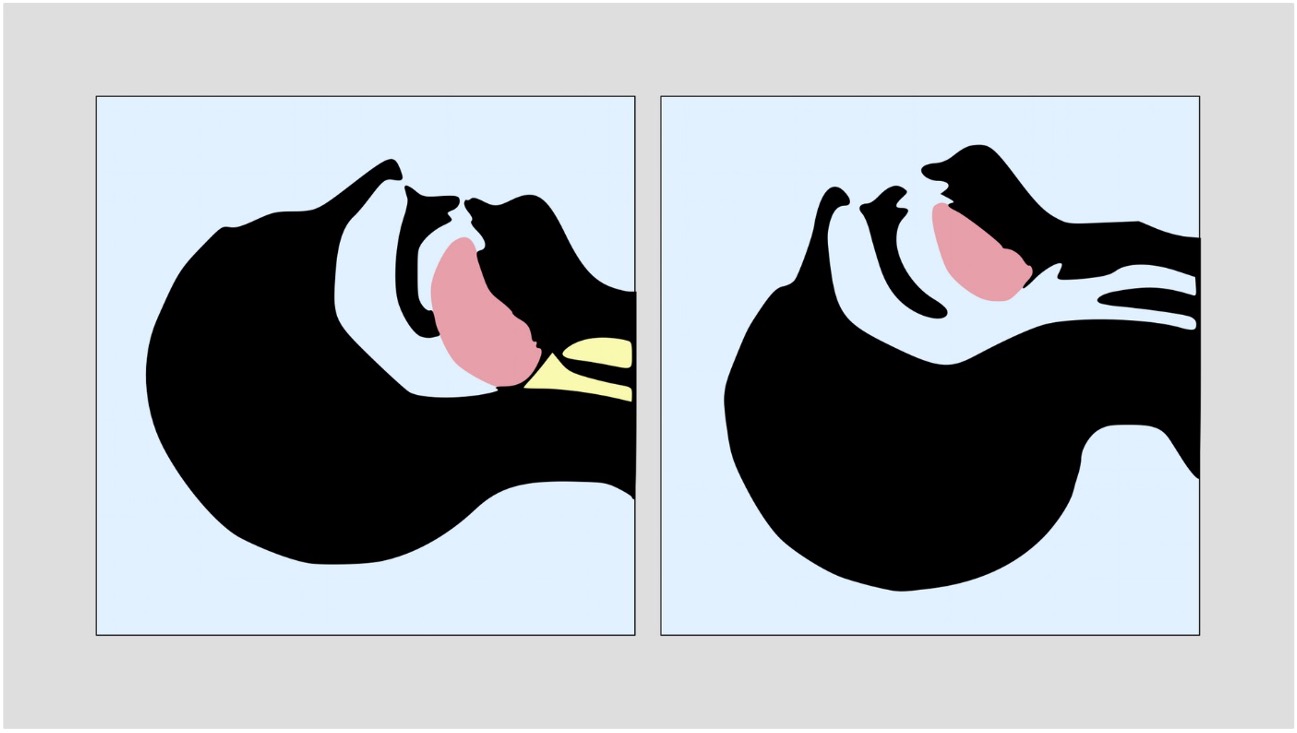

A low-pitched sound due to obstruction in the nasopharynx or oropharynx, sounds like nasal congestion or snoring.

High-pitched ‘musical’ sound when bronchial airways are narrowed – can be inspiratory, expiratory or biphasic. Wheeze can be heard across the lungs (e.g. asthma) or in a localised area (e.g. foreign body).

Secretions or other fluid (e.g. vomit or blood).

Airways always need the most skilled practitioner available – usually an anaesthetist or an ITU/ED specialist - to maximise the chance of first-pass success for intubation. Excessive laryngeal manipulation from repeated attempts at intubation will lead to airway oedema and inflammation, making subsequent attempts more difficult.

What will you do if there’s nobody around you? You should shout for help or pull the emergency alarm. Don’t be afraid to do this if you need to, nobody will judge you for getting help if you’re worried!

The following are techniques only to maintain airway patency:

Whereas these also protect the airway:

Protective measures maintain patency, but are also a completely closed circuit, so prevent secretions/vomit from entering the airway or air from inflating the stomach. They are used for definitive airway protection.

Group causes based on:

If breathing is insufficient to oxygenate the blood, the patient can quickly go into cardiac arrest.

Cyanosis is a blue-purple discolouration caused by a lack of oxygen to the affected tissue. This could be due to poor oxygen uptake in the lungs, poor transport of oxygen bound to haemoglobin, or poor offloading of oxygen to tissues.

Commonly this affects the skin of the peripheries (e.g. fingers and toes) in peripheral cyanosis, or mucous membranes (e.g. lips and tongue) in central cyanosis.

Normal inspiration is performed by the diaphragm and external intercostal muscles. Expiration is a passive process where the lungs recoil.

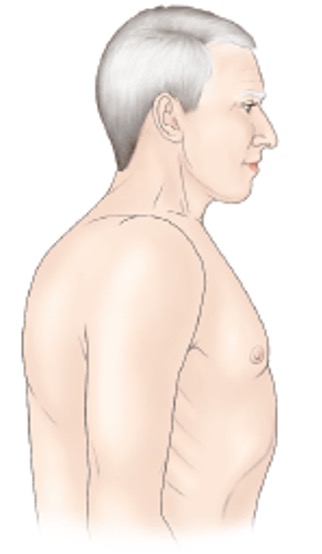

Using accessory muscles to aid breathing indicates increased work of breathing. Accessory muscles of respiration include the sternocleidomastoid, scalene, pectoralis major and trapezius muscles – these assist in inspiration. Abdominal muscles such as rectus abdominis and the obliques can assist with active expiration.

Sitting in the tripod position makes the use of accessory muscles easier, to help with increased work of breathing.

The image also shows pursed-lip breathing, which help to make breathing slower and more controlled.

Classical finding in COPD. The lungs are unable to exhale fully due to reduction in elastic recoil and are therefore chronically overfilled with air.

Respiratory investigations should focus on assessing lung ventilation and tissue perfusion.

When asked about investigations you would perform it is best practice to give them in order of invasiveness/complexity - i.e. start with things you can do at the bedside. If you jump straight to imaging you'll miss out the basics!

Think the five S's... bedSide tests (e.g. basic observations, ECG), Swabs (wounds, throat etc), Samples (bloods, urine, stool etc), Scans (radiological imaging), Surgery (biopsies, excisions and exploratory surgery)

If the patient is hypoxic, provide supplemental oxygen 15L/min via a non-rebreathe mask and titrate according to response.

Patients with COPD who are unwell and hypoxic can still be started on 15L/min. Due to the risk of hypercapnia it is advised to use a 24-28% venturi mask and aim for O2 saturations 88-92%. ABGs allow monitoring of CO2 levels to assess CO2 retention.

Other treatments should be provided depending on the suspected cause, such as:

Reduced blood volume.

Blood volume remains normal, but fluid is distributed to the wrong places.

Occurs in any condition where the heart cannot maintain adequate cardiac output.

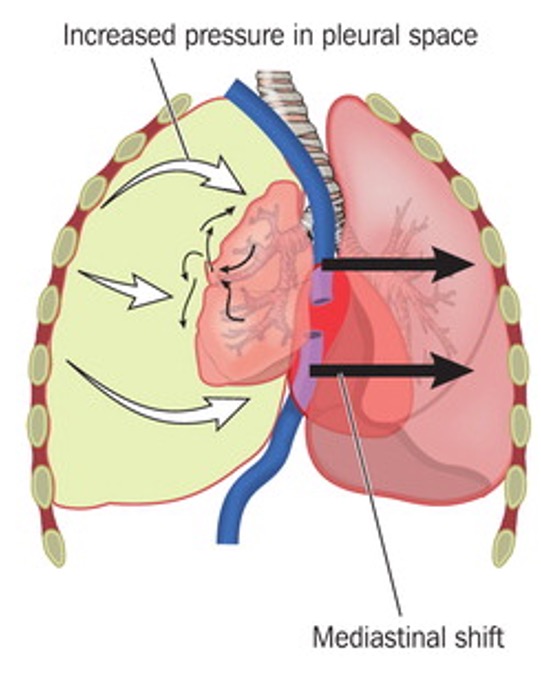

Obstruction of the heart's ability to pump or of the outflow of blood through the great vessels.

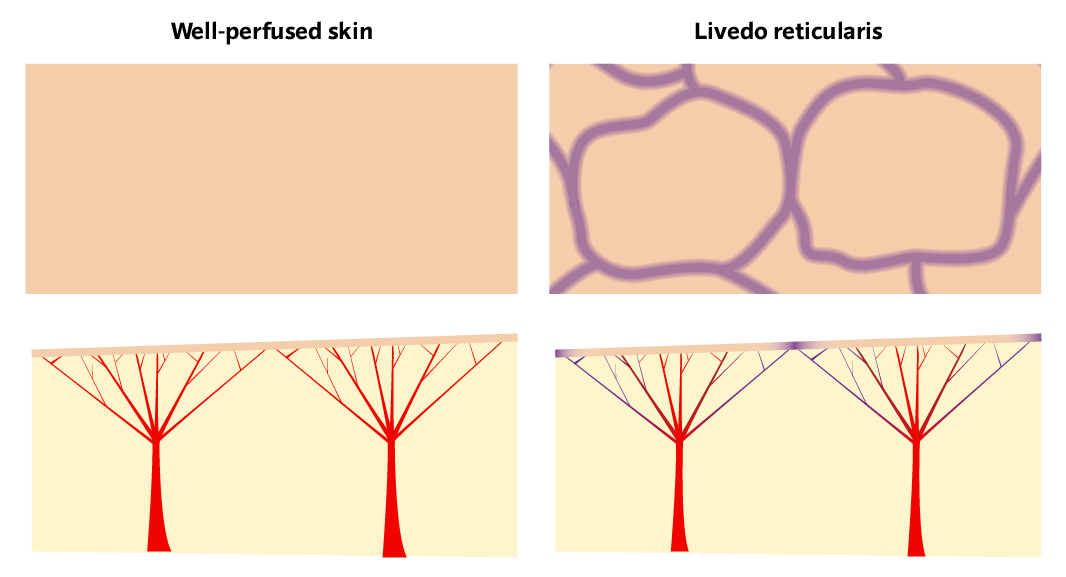

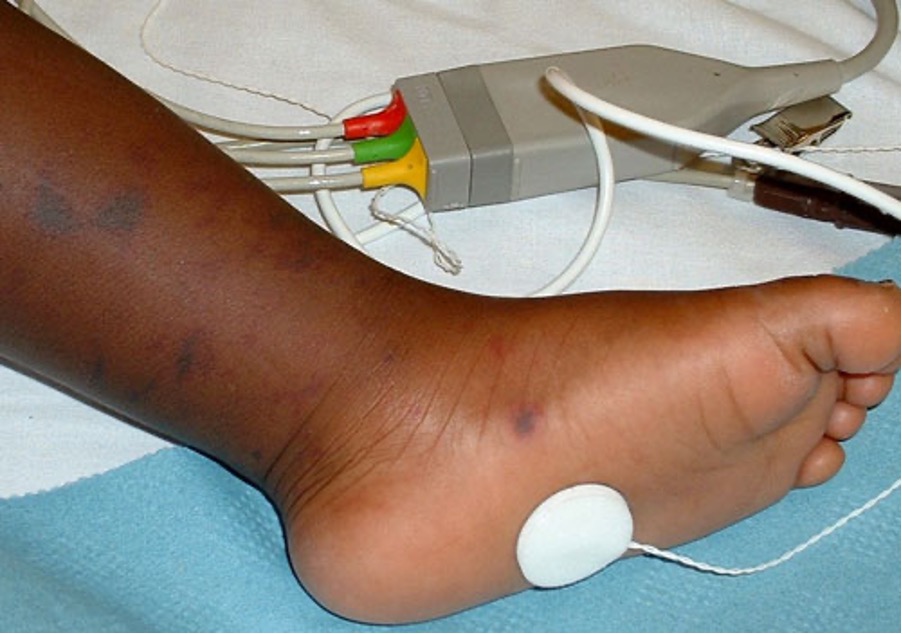

Mottling of the skin (livedo reticularis) is a classic skin finding in shock or other states of poor perfusion.

Each capillary bed is like a tree, the arteriole is the trunk with all the capillaries reaching out up to the skin. There are lots of these next to each other, each supplying a small area of the skin.

When there is poor tissue perfusion, the capillary beds furthest from the arteriole will be the first to be affected by the low oxygen saturation. The periphery of each capillary bed receives less oxygen and the skin it supplies begins to cyanose. But the centre of each arterial "tree" is still getting enough oxygen.

So looking from the surface you'll see a ring of cyanosis, with normal skin in the centre. With all these "trees" next to each other the pattern looks like a net of cyanosis (reticular pattern).

Gauge and flow rate have no real correlation, gauge is an arbitrary number.

The difference between 18G and 16G doesn’t sound particularly significant. But 16G actually has twice the flow rate of 18G. This makes a huge difference for rapid fluid replacement and resuscitation.

| Gauge | Colour | Flow rate |

|---|---|---|

| 14G | Orange | 240 ml/min |

| 16G | Grey | 180 ml/min |

| 18G | Green | 90 ml/min |

| 20G | Pink | 60 ml/min |

Day-to-day on the wards you will see most patients with a pink cannula (20G) for giving normal slow IV infusions. You may see blue cannulas (22G) for older adults with fragile veins. Grey or orange cannulas are considered "wide-bore" and should always be used for resuscitation, rapid fluid replacement, blood transfusion, surgery and trauma.

If the patient has low blood pressure (or signs of compensated shock), or fluids form part of a treatment protocol (e.g. hyperglycaemia) then start fluid resuscitation through the cannula you inserted.

Don’t give fluid unnecessarily due to the risk of circulatory overload

Blood products should always be given in haemorrhage, it is best practice to replace 'like-for-like' where possible.

In some settings, especially trauma surgery, autologous blood transfusion can be performed. As blood is suctioned from the surgical field, a cell salvage machine can extract the red blood cells and recycle them to be transfused back into the patient.

These are drugs which cause peripheral vasoconstriction (vasopressors) and increase the force of contraction of the heart (inotropes). They may act solely as a vasopressor or inotrope, or perform a mix of both actions.

Examples include: adrenaline, noradrenaline, dopamine, phenylephrine, ephidrine.

They should only be initiated after consultation with a senior and under supervision.

Take haemostatic measures.

The primary focus of circulatory issues is on shock (when blood pressure is low). Don't forget it is also possible to get a hypertensive crisis with a high blood pressure, requiring antihypertensive treatment.

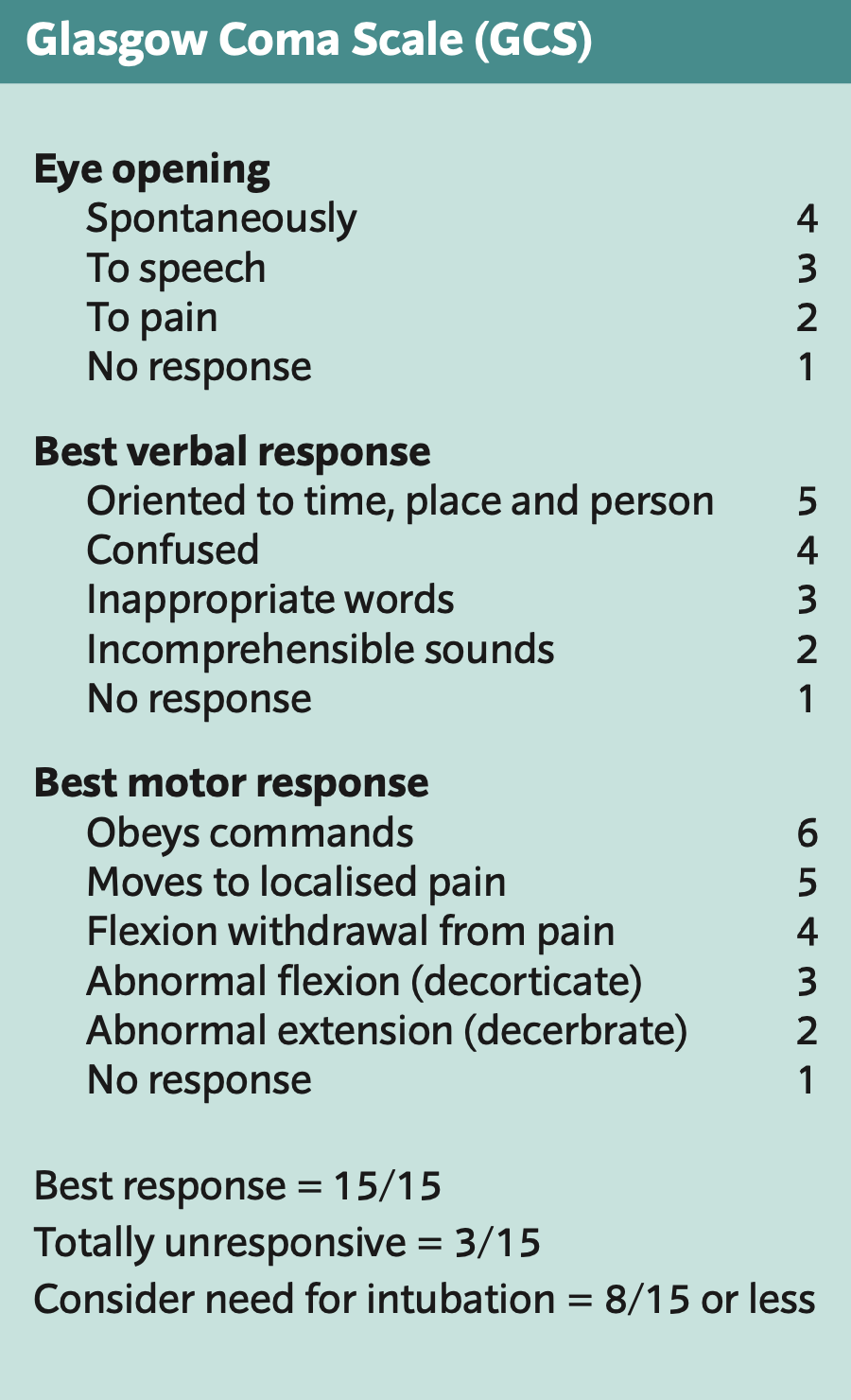

If the patient is unresponsive or only responsive to pain (GCS below 8), intubation is usually necessary.

Perform a rapid whole-body inspection to check for other injuries or clinical signs – from top to bottom, front to back.

Expose the patient appropriately:

If you've found any more clinical signs, check you're still treating for the most likely diagnosis. Focus on treating the unerlying condition (e.g. sepsis).

Once you've finished your first pass of the A-E assessment you can focus more on what led to this deterioration event.