It's important for all healthcare workers to have an understanding of how to identify a patient that is in cardiac arrest, or at risk of imminent cardiac arrest, using the A-E assessment approach. You should then be able to call for support from the cardiac arrest team and perform CPR to begin resuscitation of a patient while waiting for help to arrive.

Be aware of which patients on your ward are at risk of cardiac arrest:

You should be able to perform an ABCDE assessment to identify cardiac arrest. The key features you may find are:

Quickly assess patient response using the AVPU scale.

If a patient is unresponsive, shout for help and assess if they are breathing.

Lean over the patient and place your cheek above their mouth and nose, looking down towards their chest.

If the patient isn't breathing, or their breathing is shallow/irregular, start chest compressions immediately. Get help by shouting or pulling the emergency alarm. Get them to call the cardiac arrest team and bring the crash trolley to you. DO NOT STOP compressions while talking to other team members.

If the patient is not breathing, you don't need to feel for the pulse before starting compressions.

Feeling the pulse is most useful during rhythm checks in the cardiac arrest algorithm, to distinguish between an arrhythmia compatible with life or a pulseless rhythm. It's preferable to feel for a strong central pulse, e.g. the carotid pulse in the neck.

Once you've recognised a patient is in cardiac arrest (or arrest is imminent) you should start chest compressions and get urgent help.

Shout for help and pull the emergency buzzer to alert the team in the area.

When the team arrive, while performing compressions, tell them to:

Once the 2222 call has been placed, the cardiac arrest team will respond. They are made up of:

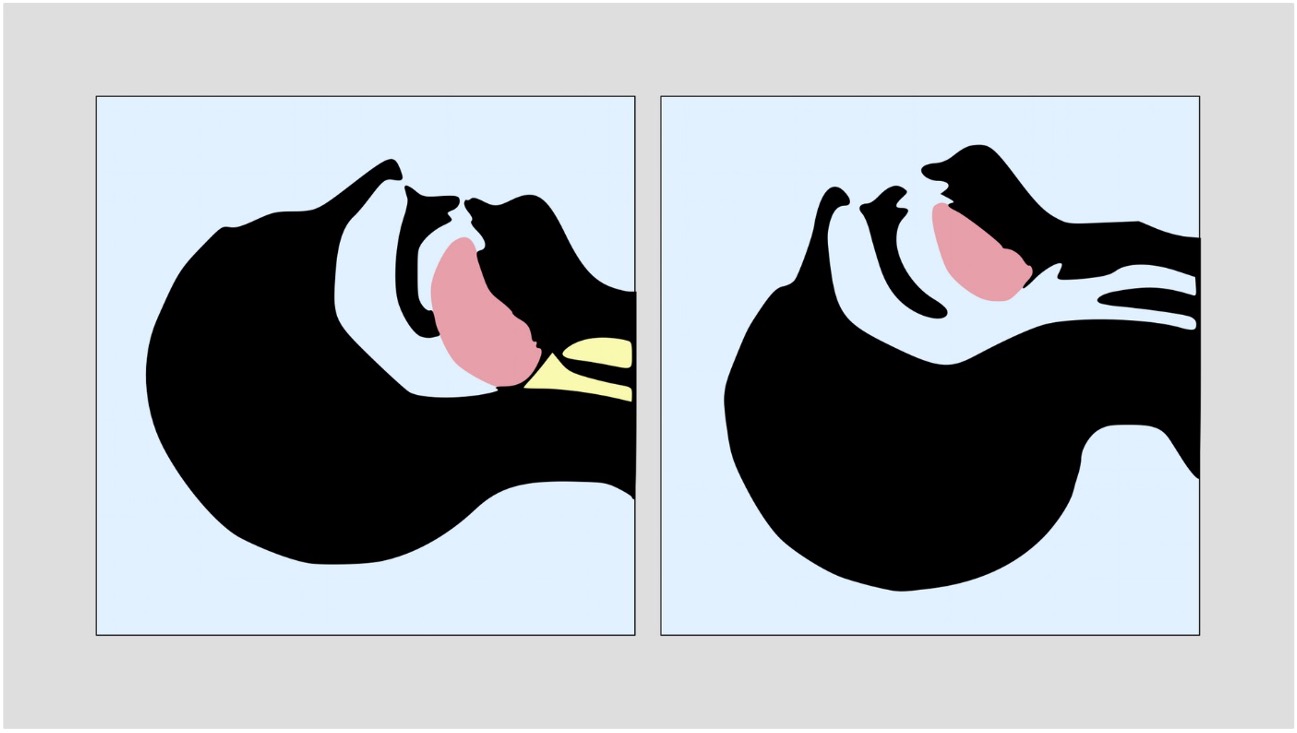

A patient in cardiac arrest is unlikely to be able to maintain their own airway. There are several methods we can use to maintain a patient's airway while waiting for senior support.

After securing any unconscious patient’s airway, you must decide whether they require passive or active ventilatory support.

A patient in cardiac arrest will not be breathing on their own and will need active ventilation.

If you have issues ventilating a patient, get senior help quickly!

In the interim:

The patient may require intubation when help arrives.

Ensure chest compressions are high-quality, this means:

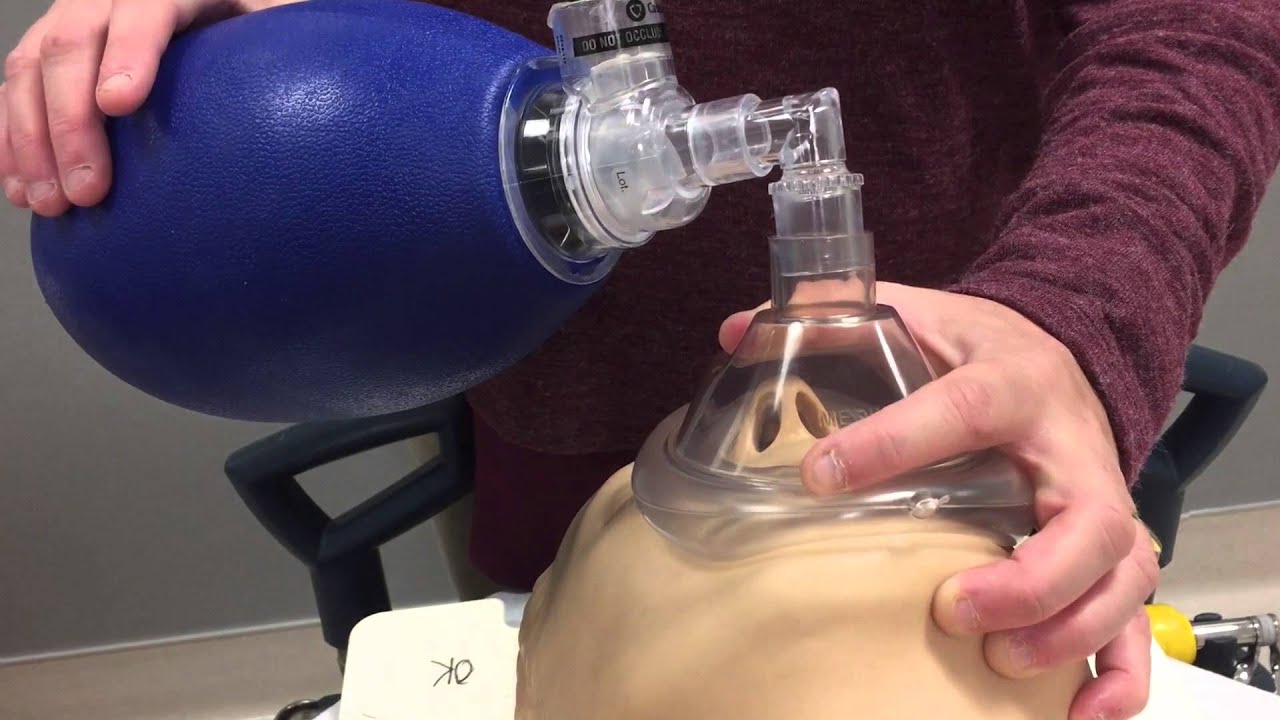

CPR should initially be performed at a ratio of 30 compressions to 2 breaths. Breaths can be delivered via a bag-valve mask, with or without adjuncts such as OPAs or NPAs.

Once a more definitive airway is in place (either a supraglottic airway or an endotracheal tube), perform continuous compressions, with continuous ventilation at ~10 breaths per minute.

Performing chest compressions is very tiring, so staff should rotate who is performing compressions to ensure they are always high quality. The team leader should frequently switch people in and out of performing compressions.

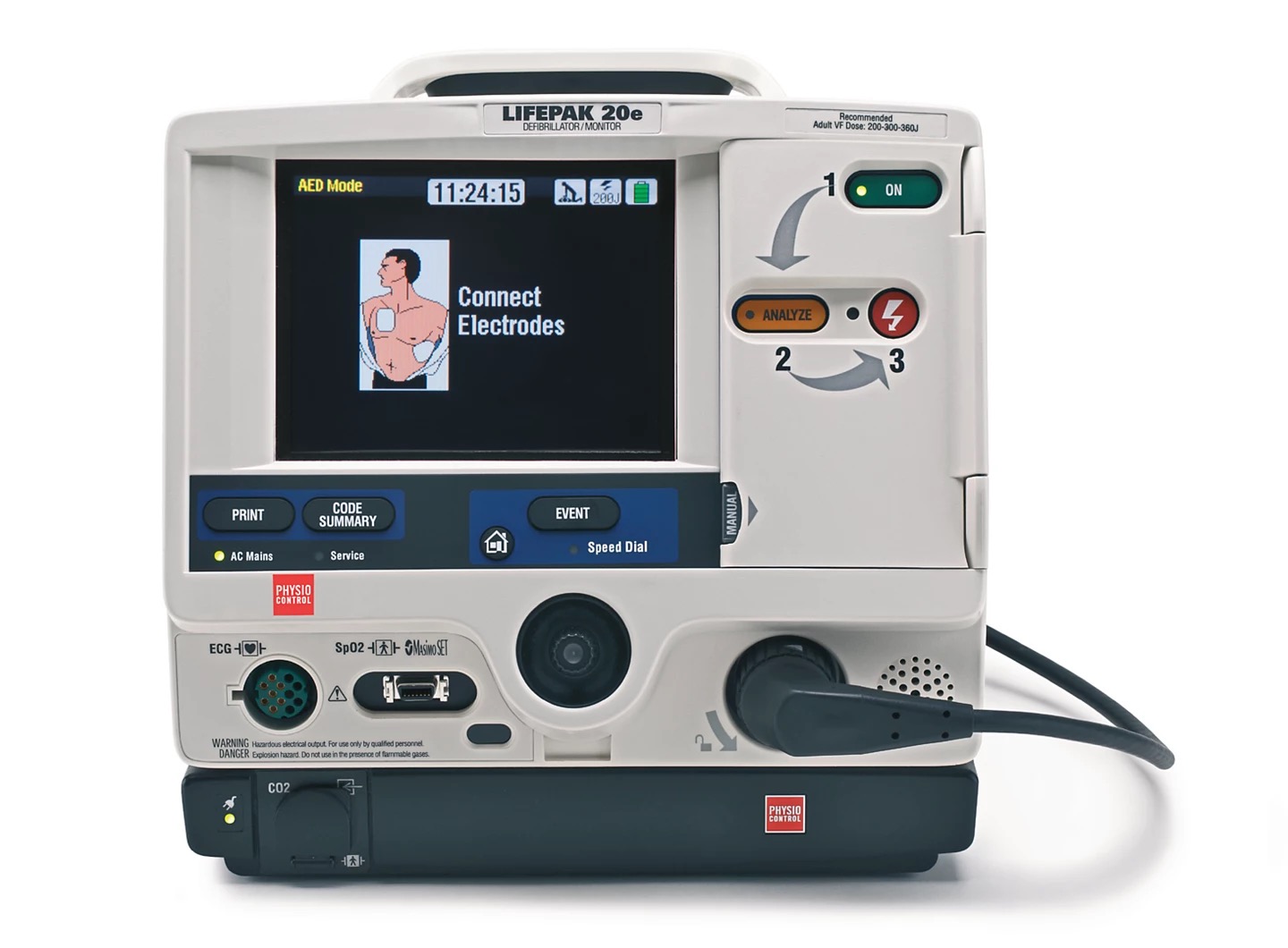

Attach the pads in order to get an ECG rhythm on the defibrillator monitor. Most devices also allow you to attach an oxygen saturation probe and blood pressure cuff. Some advanced devices may also allow for additional monitoring such as end-tidal CO2 and temperature probes.

Ensure the defibrillator pads are stuck firmly to the patient, you may need to wipe/dry the chest and shave any hair. The pads can be attached in a variety of positions:

Defibrillators in automatic mode (AED) will analyse the ECG rhythm automatically and recommend a shock if appropriate. If you use the defibrillator in manual mode, you will need to assess the ECG rhythm yourself and decide what to do.

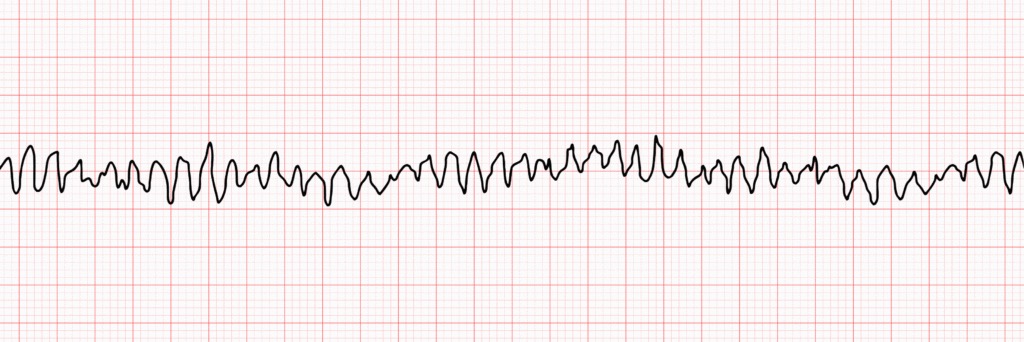

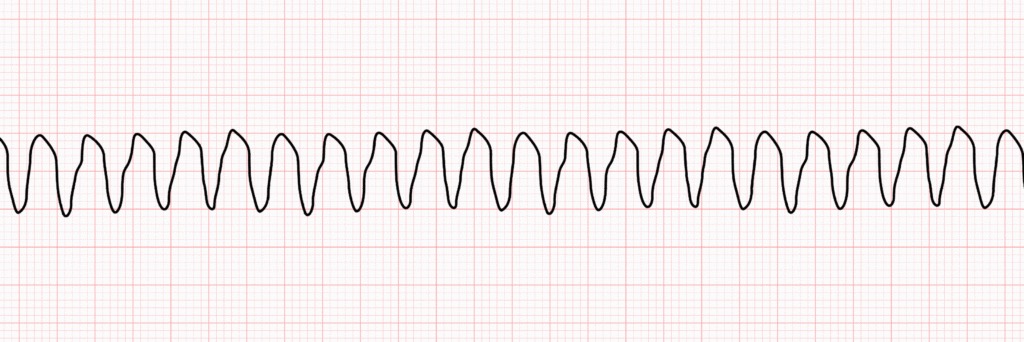

An abnormal heart rhythm in which the ventricles twitch, rather than performing proper, effective beats.

Often comes on shortly after a heart attack (MI) and is the leading cause of sudden cardiac death.

Tachycardia (>100bpm) caused by irregular electrical impulses in the ventricles.

If this rhythm is associated with no pulse, it is classified as pulseless VT and can be shocked.

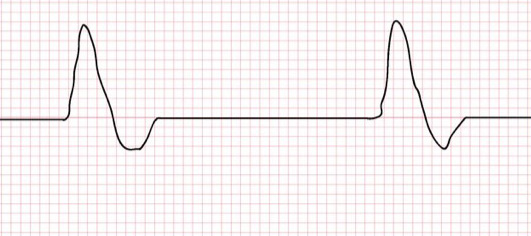

The heart’s electrical activity is too weak to continue pumping blood throughout the body.

The electrical system is working fine and may show a rhythm normally compatible with life - it’s just not powerful enough, therefore a shock will not help in this instance.

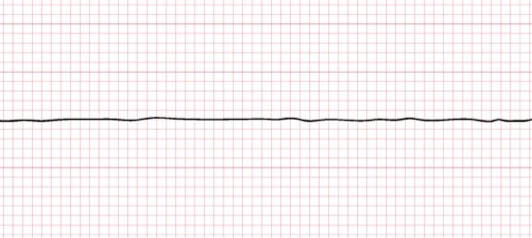

The heart’s electrical system has shut down and there is no heartbeat.

Can be the result of untreated VT or VF.

Shocking will not help, as there is no electrical activity to rectify.

The algorithm should be continued until the rhythm/pulse check shows return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) or the team decide it is appropriate to discontinue resuscitation efforts.

During the whole algorithm, the team should consider if there are any reversible causes of cardiac arrest that can be treated.

The algorithm should be continued until the rhythm/pulse check shows return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) or the team decide it is appropriate to discontinue resuscitation efforts.

During the whole algorithm, the team should consider if there are any reversible causes of cardiac arrest that can be treated.

If you achieve a rhythm compatibile with life and the patient has a pulse:

Key considerations